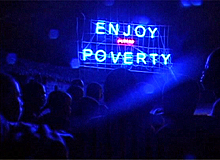

A Prior: Renzo Martens

A Prior

W]hat art does is help you reformulate concepts, ideas and beliefs and to become conscious of things, not in a visceral way alone, but in a cognitive way….[7] Perhaps Martens’ objective could be to formulate a mediation, to create a means through which to see reality, to understand and interpret it.

...

Emerging from the first of our two lengthy conversations was an artist with a decisive point of departure: making use of the same strategy as his ‘fellow’ photographers and journalists, Martens refers to his film as a tautology. “As the producer of the film, you are always implicated. You are always involved. Many filmmakers and photographers try to cover this up.” According to Martens, declaring your own position is the ultimate prerequisite for opening up an external reality. Moreover, on the part of the filmmaker, exposing or not exposing one’s own position is often tied up with an economic implication. As a result, the position of the photographer or filmmaker in this context can only be recognized when it is lucrative. For example, in presenting help by a relief worker, the latter (usually a white man or woman) is put in the image, but where exploitation is being presented as the subject matter, you never see a white person in the image. Martens refers to Tillim, the white South African whose photographs were shown at Documenta, and how Tillim ensures that there is never a white journalist to be seen in any of his photographs, even if, at the events he photographed, he was surrounded not only by hordes of black protesters, but also by hordes of white photographers. According to Martens, this is only because Tillim wants to sketch the situation as an external reality, with which the future buyer of the work has or wants no real relationship. The person who purchases or sees the work will see the African situation as an outsider, certainly not as someone who is in fact involved with it, let alone contributing to its perpetuation.

Martens moreover has clear doubts about the potential of showing the suffering and pain of others in images, and to support his thinking, he refers, among others, to Susan Sontag. As Martens puts it, Susan Sontag described it well in her book, Regarding the Pain of Others. It is, in fact, impossible to visualize suffering. “It seems too simple to elect sympathy (as a feeling generated by photographs). The imaginary proximity to the suffering inflicted on others that is granted by images suggests a link between the faraway sufferers – seen close-up on the television screen – and the privileged viewer that is simply untrue, that is yet once more a mystification of our real relations to power. So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence. To that extent it can be (for all good intentions) an impertinent – if not inappropriate – response. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same maps as their suffering, and may – in ways we might prefer not to imagine –be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”[8] In other words, Martens agrees with Sontag that the pain and suffering of others is in fact impossible to depict.

...The segment on the art gallery is interesting. In it, the gallery is exhibiting ‘artistic’ photographs of workers in appalling conditions. They seem virtual slaves. Taken by the wife of the manager of the plantation where the workers were being exploited like slaves, the photographs are being sold for $600 apiece at an opening at a local gallery, to buyers who include the plantation owner himself. In this scene, Martens’ investigation reaches a climax. Concurrently, it is here that cynicism also reaches its apex – not Martens’ cynicism, but that of the exploiter and the Westerner with the clear conscience, aware of no wrongdoing whatsoever. Almost equally repulsive, or in any case hard to digest – on Christmas Eve – is a scene in which a few local men, on Martens’ own instructions, take photographs of malnourished and literally dying toddlers. They emphatically tell their fellow villagers how they will pay nothing for their photographs, cannot give them anything at all, cannot be of any possible use to them and will themselves only earn a penny from the commercialization of their poverty. These are horrible situations, and it is at moments like these that I suddenly look at what I am seeing with different eyes. I feel very involved and responsible for what is happening, and I understand that Martens here reaches his goal.

Martens compares his tactics with those of a satirical tradition, as he tells me about A Modest Proposal,[9] the satirical pamphlet published by Jonathan Swift in 1729, describing how parents should best serve their children to be eaten at fancy London dinner tables, rather than let them be a burden to themselves or to the state. At the time, the pamphlet was dismissed as satanic and immoral, but its intention was to open people’s eyes to the misery prevailing in Ireland in the eighteenth century. With this comparison, Martens sees his position as a filmmaker as deviating from that of ordinary reporters because he brings himself into the image while showing what is happening. By making a film about its own broader parameters, elements that are normally obscured become obvious and visible. In this way, one’s sense of involvement also becomes far greater.

W]hat art does is help you reformulate concepts, ideas and beliefs and to become conscious of things, not in a visceral way alone, but in a cognitive way….[7] Perhaps Martens’ objective could be to formulate a mediation, to create a means through which to see reality, to understand and interpret it.

...

Emerging from the first of our two lengthy conversations was an artist with a decisive point of departure: making use of the same strategy as his ‘fellow’ photographers and journalists, Martens refers to his film as a tautology. “As the producer of the film, you are always implicated. You are always involved. Many filmmakers and photographers try to cover this up.” According to Martens, declaring your own position is the ultimate prerequisite for opening up an external reality. Moreover, on the part of the filmmaker, exposing or not exposing one’s own position is often tied up with an economic implication. As a result, the position of the photographer or filmmaker in this context can only be recognized when it is lucrative. For example, in presenting help by a relief worker, the latter (usually a white man or woman) is put in the image, but where exploitation is being presented as the subject matter, you never see a white person in the image. Martens refers to Tillim, the white South African whose photographs were shown at Documenta, and how Tillim ensures that there is never a white journalist to be seen in any of his photographs, even if, at the events he photographed, he was surrounded not only by hordes of black protesters, but also by hordes of white photographers. According to Martens, this is only because Tillim wants to sketch the situation as an external reality, with which the future buyer of the work has or wants no real relationship. The person who purchases or sees the work will see the African situation as an outsider, certainly not as someone who is in fact involved with it, let alone contributing to its perpetuation.

Martens moreover has clear doubts about the potential of showing the suffering and pain of others in images, and to support his thinking, he refers, among others, to Susan Sontag. As Martens puts it, Susan Sontag described it well in her book, Regarding the Pain of Others. It is, in fact, impossible to visualize suffering. “It seems too simple to elect sympathy (as a feeling generated by photographs). The imaginary proximity to the suffering inflicted on others that is granted by images suggests a link between the faraway sufferers – seen close-up on the television screen – and the privileged viewer that is simply untrue, that is yet once more a mystification of our real relations to power. So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence. To that extent it can be (for all good intentions) an impertinent – if not inappropriate – response. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same maps as their suffering, and may – in ways we might prefer not to imagine –be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”[8] In other words, Martens agrees with Sontag that the pain and suffering of others is in fact impossible to depict.

...The segment on the art gallery is interesting. In it, the gallery is exhibiting ‘artistic’ photographs of workers in appalling conditions. They seem virtual slaves. Taken by the wife of the manager of the plantation where the workers were being exploited like slaves, the photographs are being sold for $600 apiece at an opening at a local gallery, to buyers who include the plantation owner himself. In this scene, Martens’ investigation reaches a climax. Concurrently, it is here that cynicism also reaches its apex – not Martens’ cynicism, but that of the exploiter and the Westerner with the clear conscience, aware of no wrongdoing whatsoever. Almost equally repulsive, or in any case hard to digest – on Christmas Eve – is a scene in which a few local men, on Martens’ own instructions, take photographs of malnourished and literally dying toddlers. They emphatically tell their fellow villagers how they will pay nothing for their photographs, cannot give them anything at all, cannot be of any possible use to them and will themselves only earn a penny from the commercialization of their poverty. These are horrible situations, and it is at moments like these that I suddenly look at what I am seeing with different eyes. I feel very involved and responsible for what is happening, and I understand that Martens here reaches his goal.

Martens compares his tactics with those of a satirical tradition, as he tells me about A Modest Proposal,[9] the satirical pamphlet published by Jonathan Swift in 1729, describing how parents should best serve their children to be eaten at fancy London dinner tables, rather than let them be a burden to themselves or to the state. At the time, the pamphlet was dismissed as satanic and immoral, but its intention was to open people’s eyes to the misery prevailing in Ireland in the eighteenth century. With this comparison, Martens sees his position as a filmmaker as deviating from that of ordinary reporters because he brings himself into the image while showing what is happening. By making a film about its own broader parameters, elements that are normally obscured become obvious and visible. In this way, one’s sense of involvement also becomes far greater.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home